Brain Tumours

Being diagnosed with a brain tumour can be a frightening experience, with frequent association with the sense of hopelessness that comes when unexpectedly faced with a little known but formidable adversary, and is often a genuine trial of courage and strength for the entire family.

Despite tremendous advances in medicine and clinical research in recent times, affliction with a brain tumour still very much requires a well-

What is a Brain Tumour?

Brain tumours may occur at any age, and do not appear to show predilections for ethnic groups or gender. Though there may be certain associations between the occurrence of brain tumours and a history of exposure to harmful factors including radiation and certain chemicals, as well as possible genetic predisposition, the reason for their occurrence remains largely unexplained.

Benign brain tumours are generally not infiltrative in character, grow relatively slowly, and are usually amenable to complete surgical removal, and sometimes to non-

Malignant brain tumours are generally infiltrative in character, grow relatively quickly, and usually require more than surgical treatment alone. Surgical treatment, when possible, is often followed by radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy. They carry a relatively negative prognosis in all respects, and some sort of permanent disability to various extents usually remains following treatment.

Primary brain tumours refer to those which arise within the brain and its membranes itself, or from primitive developmental residual remnants and they do not usually metastasise outside the central nervous system. The majority of primary brain tumours, however, are either progressively malignant, or recurrent with increasing grades of malignancy in spite of early diagnosis or initial low-

Secondary brain tumours refer to metastases from malignant tumours in other areas of the body.

Symptoms

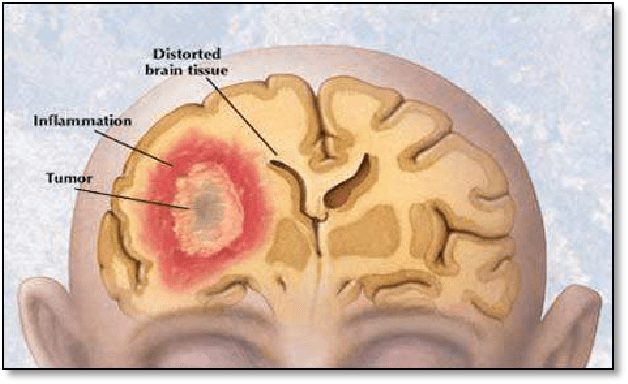

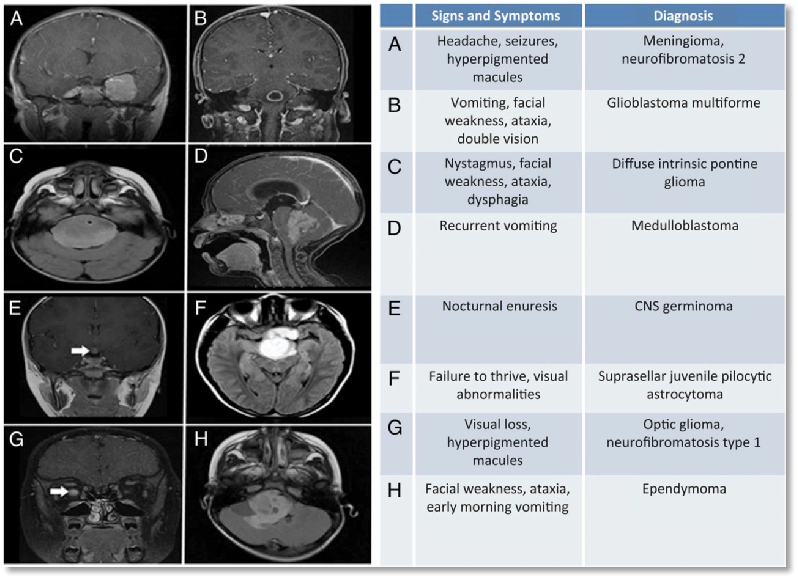

The symptoms of a brain tumour can develop gradually or quickly depending on the type of tumour. Headaches are a common symptom, but usually not the only symptom. Changes in personality and having a seizure (fit) are other general symptoms.

A brain tumour can also lead to increased pressure in the skull. The main symptoms of this are headaches, sickness, vomiting and confusion.

Other symptoms depend on the position of the tumour, and how it prevents that part of the brain from working properly. Tumours in the cerebrum can cause weakness on one side of the body, problems with speech, vision and memory. Tumours in the cerebellum, and in the brain stem, can lead to problems with coordination, walking and unsteadiness.

A tumour in the pituitary gland can cause different hormone related symptoms, such as infertility but can also cause tunnel vision. A tumour that affects the hearing nerve causes hearing loss.

Diagnosis

When there is suspicion of a brain lesion, the patient should identify as soon as possible a physician (e.g: GP) who should quickly get a brain scan and refer him to a specialist (Neuro-

Some scans are difficult to interpret and some tumours are difficult to grade. You need to know the type of tumour and the grade in order to assess the need for urgent action or whether a slower approach is acceptable.

This is easily said but difficult to do because there is strong demand for scarce resources.

Get a second opinion.

The full diagnostic work-

Complete medical history with physical and neurological examination.

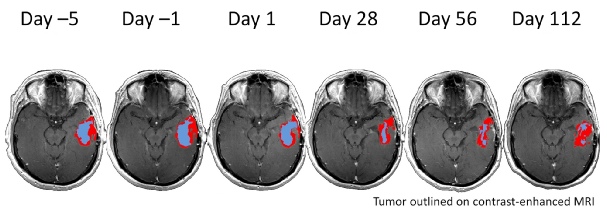

Radiological evaluation: the preferred diagnostic investigation is magnetic resonance imaging without and with contrast enhancement. The advantages here lie in the vast amount of detail that can be visualised without exposure to ionising radiation.

Disadvantages are:

This cannot be used for those carrying some kind of metal implants even if in most cases is safe, except for a few times. The radiologist should be always informed of any metal or electronic device (pace-

It can be a very uncomfortable experience for those who are claustrophobic, in this case the open MRI can be an alternative option

Lack of widespread availability

The relatively high cost of such an investigation

Another widely use diagnostic tool is computerised tomography. Advantages here are excellent imaging of bony structures, short duration of the procedure, greater availability and it is cheaper.

In specific cases a lumbar puncture can be useful to measure the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) that bathes the brain and spinal cord, and is possible to analyse a small amount allowing a differential diagnosis between infections and tumours.

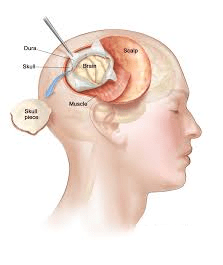

Surgical removal of the tissue sample through a biopsy or in the contest of a surgical resection, whenever it is possible: the pathological diagnosis is the important final step allowing a differential diagnosis between eventually benign/malign tumours. The neurophatologist will see the type of cells present, their abnormalities and speed of growth, plus other biological features that will allow tumours to be rated and graded from the least malignant to the most aggressive ones.

Whenever the surgical approach is not possible, the radiological diagnosis can be a satisfactory criterion for the diagnosis itself, based on the features of the lesions that can be highly indicative of their nature.

Should the tumour turn out to be a benign one, late diagnosis does not always imply a negative prognosis. Should the tumour, however, turn out to be a malignant one, a possible consequence of late diagnosis is that at times, even at the point of first presentation of symptoms, the tumour is already either much too large with massive infiltration, or spread over many locations in the brain, thereby precluding effective neurosurgical intervention of any kind right from the start.

Treatment

An interdisciplinary team (neurosurgeons, clinical and medical oncologist, diagnostic and interventional neuroradiologists, neuro-

Before agreeing on a treatment regimen, thorough counselling is highly recommended regarding available treatment options, the possibly benefits, and how far the surgical prognosis can match personal expectations

The correct treatment depends on the nature, size and location of the tumour, on the clinical condition of the patient and on the age.

The options available are: neurosurgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy, but is strongly encouraged to provide the patient with more treatment options, which unfortunately are not available in all the Oncology Centres but only in the Major Research ones, offering the possibility of being enrolled in a clinical trials that are designed to evaluate the effectiveness of promising new treatments with potential benefit.

The Alison Fracella Research Trust supports such work at The Royal Marsden Hospital. You can see a report on this workhere. Other organisations are carrying out research in this area. Recently The Institute of Cancer Research published a report relating to mechanisms behind childhood glioblastoma. Their work may lead to clinical trials within two to three years.

Unfortunately right now it is not possible “to cure” most of brain tumours because their infiltrative partner in the surrounding tissue and their intrinsic resistance to treatments, besides the difficulty found by most of the drugs to cross the blood brain barrier (BBB).

FAQ

To date it is not clear why brain tumours occur. There are theories revolving around possible connections to certain genetic traits, familial clusters, and prior exposure to industrial chemicals, etc., but their roles are not entirely certain. A history of exposure to ionising radiation does correlate in some cases with an increased chance of developing a brain tumour. Instead of dwelling on what cannot be influenced as it has already occurred, it is better to shift the focus to the options to deal with it. The arsenal available at the disposal of neurosurgeons today is indeed formidable and expanding by the day—you are not alone in your fight.

The focus here, at least in the beginning, should revolve around what can be done for you, what treatment options are available to you, and how to arrive at a decision that lies in your best interests along with your attending physicians. Despite the large volume of data published, the “how-

Percentages are derived from statistics, and calculated from a large number of documented observed and follow-

A second opinion is certainly warranted, especially in difficult cases involving more sensitive locations and disputable therapeutic strategies. But it is wise to remember that the best approach would be to settle on the neurosurgeon with the most documented experience in that particular area of expertise. Too much of drifting from neurosurgeon to neurosurgeon is not advisable, and can result at times in serious loss of time, besides compounding the already present feelings of confusion and uncertainty.

Once the well thought out decision has been taken to implement a therapeutic option, it is advisable to go ahead with it without much further beating about the bush. Uncertainty, confusion, and a lack of confidence are natural, but should not come in the way of expressing your trust in your chosen neurosurgeon, and giving them leeway to carry through the treatment at the highest possible standards and in your best interests. There are questions to which they have answers… and there are questions to which none exist at the moment. It may prove difficult, but this ought to be remembered and respected.

The “steroids” you are requested to take are not the ones that are used in bodybuilding, etc. The ones you will be given are different, and have other properties that are highly beneficial for you. They help in significant reduction of swelling and oedema, which is very important before an operation. Further, the natural reaction to any body tissue to trauma of any kind—including that which is unavoidably inflicted during surgery—is to swell. After a surgery on the brain, therefore, it is very important to take this medicine to minimise the amount of post-

The first few days will be spent recovering from the surgery. Once this period is over and you have been mobilised and are stable health-

Whether you have had fits before or not, after a large surgery, depending on the location of the tumour, it is at times prudent to give post-

No medicine, however relatively harmless, is without side effects. What is important is to weigh the potential benefits against the possible undesirable side effects, and decide on the option that offers you the most with minimal harm incurred. When chemotherapy has been suggested, this has been done taking everything into due consideration.

The potential side effects are many, but the one that can be life threatening is the risk of bleeding secondary to a reduction in blood platelet levels which is often seen during chemotherapy.

There are certainly undesirable side effects, but what is important is to weigh the potential benefits against the possible undesirable side effects, and decide on the option that offers you the most with minimal harm incurred. When chemotherapy has been suggested, this has been done keeping your best interests in mind.

The potential side effects are many, but the ones that you should certainly bear in mind is the potential damage to cognitive functions, and the fact that following radiotherapy, future surgery becomes more difficult and complicated.